Humans and Insects in the Natural World: The Entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre and His Fame in Japan

Books Environment- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

A Legend of Entomology

The renowned French entomologist Jean-Henri Fabre (1823–1915) holds a special place in the hearts of generations of insect-loving Japanese. The translation of his 10-volume Souvenirs entomologiques (published in English as Fabre’s Book of Insects) remains a favorite among bug-sleuths of all stripes in Japan for its engaging descriptions of the anatomy and behavior of a host of insects gleaned from Fabre’s pioneering research.

In Japan, the long list of Fabre fans includes Yōrō Takeshi, a well-known philosopher and professor emeritus at the University of Tokyo, and Okumoto Daisaburō, a specialist in French literature and professor emeritus at Saitama University. Both men were drawn to Fabre by a lifelong interest in insects, and today the pair serve on the board of the Japan Henri Fabre Society, with Okumoto as president. The two recently published Fāburu to Nihonjin (Fabre and the Japanese), a collection of their wide-ranging discussions about the famed French entomologist and his influence on Japanese society.

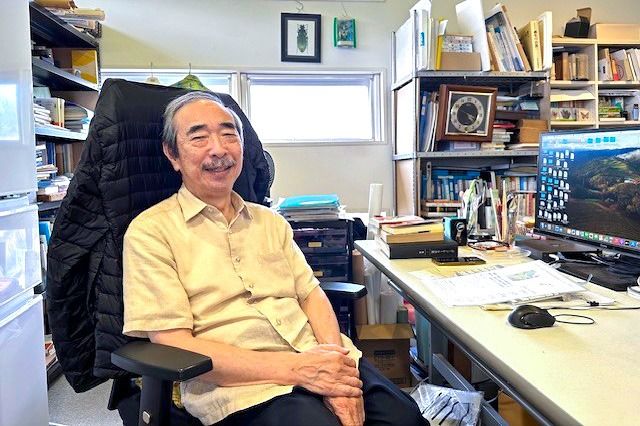

Okumoto Daisaburō at his office at the Fabre Insect Museum in Tokyo. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

Shared Views and a Japanese Lens

In the book, Yōrō attributes Fabre’s enduring popularity in Japan to the intimate approach he took to his subjects, noting that “Japanese and Europeans saw insects in fundamentally different ways. In France, Fabre was considered a bit of an oddball for having such a deep interest in bugs. But his research resonated with young Japanese who grew up with a cultural affinity for insects. There was a familiarity that people could relate to.”

Okumoto, who spent three decades translating Fabre’s Book of Insects into Japanese in its entirety, laments that little has changed in France in terms of people recognizing the importance of Fabre’s most important work. “The fact that few people in his homeland take the time to read it,” he states, “has kept Fabre’s achievements from receiving the recognition they deserve.”

I interviewed Okumoto in 1995 while he was president of the Japan Insect Association, during which he shared his views that the Japanese cultural tradition of living close to nature fosters a deep connection and appreciation of one’s surroundings. “There is a tendency in Japan to be detail oriented, as if observing nature through a telescopic lens,” he opined. He attributed this cultural trait to Japan’s hordes of amateur entomologists, but also went as far as to tie this fixation with details to Japan’s reputation for technical innovation in industries like semiconductors.

Okumoto pointed to the works of the eighteenth-century artist Itō Jakuchū as a glowing example of this cultural proclivity for minutia. Discussing Itō’s depiction of a cricket dangling from a vine, Okumoto noted that it is the underside of the insect that is shown, not the top as would be more typical, something he argued is a clear illustration of the painter’s close attachment to the natural world.

Reconnecting with Nature

The 1960s were a golden age of amateur entomology in Japan. Children headed in droves to parks, woodlands, and fields to collect insects for their own enjoyment, logging their findings in specimen cases as part of their summer holiday homework assignments. Economic growth had brought prosperity at the expense of environmental degradation, but the full brunt of the rampant air pollution of the era had yet to be felt and there remained a vast variety of insects to be eagerly snatched up in nets.

A family collects insects in the woods around Hakone in Kanagawa Prefecture. (© Izumi Nobumichi)

Children today, though, are left to commune with an environment scarred by widespread use of agricultural chemicals, rapid urbanization, and other issues. “The reduction in vegetation and insects is obvious,” states Yōrō in the book. Okumoto describes the situation as “material richness” amid a “deprivation of insects.”

In late July 2024, I travelled to the Fabre Insect Museum to meet with Okumoto for the first time in nearly 30 years. During our conversation the lively octogenarian spoke time and again of the changes to the wilds of Japan, saying that society now suffers from what he calls a “privation of nature.”

Reflecting on Fabre’s approach to his life and work, Yōrō in the book decries how we have become beholden to devices like smartphones for information. He lauds Fabre’s independent thinking, describing how he shunned the standard approaches of his field and set out to observe his subjects directly, conducting experiments of his own design in order to unravel the mysteries of insect behavior.

Yōrō suggests finding ways to get children to put down their devices and reconnect with nature, even if just once a week or once a month. In the same vein, Okumoto advocates a dedicated “smartphone-free” national holiday. Practicality aside, a forced decoupling from our devices to go out to collect insects makes for a compelling argument.

The Importance of Viewing Nature

Yōrō and Okumoto obviously share Fabre’s affinity for “nature, humanity, and insects.” They have a companion in another Japanese entomological luminary, Shiga Usuke (1903–2007), who in a 1996 book reflected that “people’s bond with nature revolves entirely around their relationship with insects.”

In their book, Yōrō and Okumoto share their wit and extensive knowledge, touching in their dialogue on topics ranging from native views on nature to Western values to the unquestioning trust in science and technology. Yōrō also raises the alarm about Japan’s propensity for natural disaster, stating that an eruption of Mount Fuji could occur in conjunction with major earthquakes on the Tōnankai and Nankai Troughs in the Pacific. In an unsettling coincidence, a month after the book was published, the Japanese government warned of activity on the Nankai Trough after a large earthquake struck off the coast of Miyazaki Prefecture on August 8.

Reading the text, it is hard not to come away with the feeling that Japanese today in their unquestioning adherence to rules and constant concern over how others perceive them have grown distant from Fabre’s view of nature. Yōrō seems to be saying that such a loss of independence bodes poorly for a potential strike by a massive earthquake on the capital. Modern life is largely removed from the natural environment, and few have the once prevalent understanding that nature does not conform to our expectations, which begs the question: How will such people cope when disaster does strike?

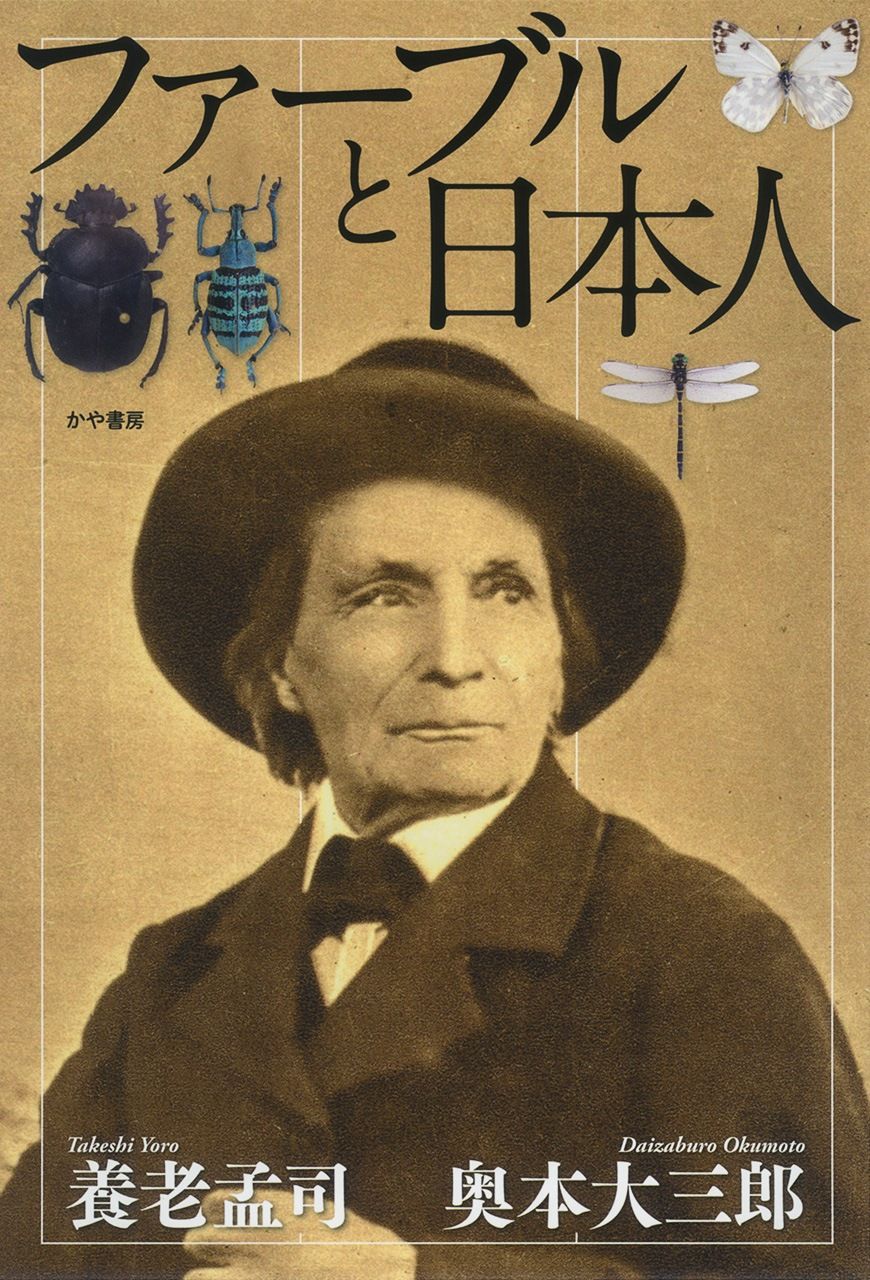

Fāburu to Nihonjin (Fabre and the Japanese)

By Yōrō Takeshi and Okumoto Daisaburō

Published by Kaya Shobō in 2024

ISBN: 978-4-910364-47-6

(Originally published in Japanese. Banner image: The cover of Fāburu to Nihonjin. Courtesy Kaya Shobō.)