Nami no Ihachi: Did a Rural Wood Carver Inspire Hokusai’s “Great Wave”?

Guideto Japan

Culture History Arts- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Forerunner to Hokusai

The new ¥1,000 banknotes that entered circulation in July 2024 feature a reproduction of The Great Wave off Kanagawa, by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) from his series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji. Commonly known as The Great Wave, it is probably the most famous ukiyo-e print in the world.

The Great Wave by Katsushika Hokusai. (Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York)

When the print first appeared, around 1832, the surging waves, depicted from below, were unconventional. But there is a wood carving with a similar design that predates the ukiyo-e by over 20 years. That work is Nami ni hōju no zu (Jewels on the Waves), carved into a transom at Gyōganji, a temple in Isumi, Chiba Prefecture, around 1807–08.

The artisan was Takeshi Ihachirō Nobuyoshi (1752–1824), eight years senior to Hokusai. This famed sculptor was mainly active in the Bōsō Peninsula in what is now Chiba Prefecture, producing over 100 wood carvings for temples and shrines in the region. His exquisite carvings of powerful waves led to his being nicknamed Nami no Ihachi (Ihachi of the Waves).

The sea at Ihachi’s birthplace, Kamogawa, Chiba Prefecture. Now, a popular surfing spot. (© Nippon.com)

Ihachi was born in 1752 in modern-day Utsutsumi, Kamogawa, Chiba Prefecture. Following an apprenticeship under a renowned sculptor in Katsuura, Ihachi struck out on his own at the age of 20. After gaining his independence, he established a workshop at his family home, not far from his beloved coast.

Ihachi is buried at the site of his former residence, which was a family workshop for five generations, into the mid-twentieth century. (© Nippon.com)

In his late twenties, Ihachi carved Tama tori ryū (Dragon Catching a Jewel), which adorns the main hall of Konjōin in Kamogawa. The temple is a stone’s throw from the family home and also boasts works by Ihachi’s descendants. (© Nippon.com)

Ihachi was a pioneer in his craft, turning commissions for carvings of sacred mythical creatures such as kirin into unique pieces that incorporate ocean waves. He continued to hone his skills throughout his life, producing increasingly realistic pieces.

Nami ni hiryū (Wave with Flying Dragons) is in the main hall of the temple of Izunadera in Isumi. This piece, carved by Ihachi when he was in his forties, can be considered a turning point in his career. The facial expressions and details such as the scales of the pair of dragons give them a sense of reality. The waves the dragons ride atop resemble talons.

The fierce pair of dragons in Wave with Flying Dragons. Ihachi’s depiction of the underside of the waves was pioneering. (Courtesy Ihachikai; © Odajima Nobuyuki)

A mythical tengu and the twelfth-century warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune appear between the two flying dragons in Tengu to Ushiwakamaru (Tengu and Ushiwakamaru). The background is incredibly detailed, and the wood grain is stunning. Ihachi’s carvings of human figures were unmatched. (Courtesy Ihachikai; © Odajima Nobuyuki)

Ihachi’s creativity developed further in his later years, after he turned 50. At Ōyamaji, a temple in Kamogawa, he carved a flying dragon on the ceiling of the roof projecting out from the front of the Fudō Hall and an “earth dragon” on the beam. Both face to the right, while a column of water spouts from the waves in the background to form clouds. The dragons guard the Nagasa Plain to the east, a rice-producing area, while the accompanying art expresses the blessing of rain.

In addition to dragons, Ihachi also carved lions and elephants. (© Nippon.com)

The temple, commonly referred to as Ōyama Fudōson has views of the nearby sea of Kamogawa. (© Nippon.com)

Depicting “Emptiness” from the Heart Sutra

After many years carving totally unique waves, Ihachi finally carved Jewels on the Waves, perhaps his greatest work, in his late fifties.

Jewels on the Waves (right-hand side) front and back. (Courtesy Ihachikai; © Odajima Nobuyuki)

Jewels on the Waves (left-hand side) front and back. (Courtesy Ihachikai; © Odajima Nobuyuki)

According to tradition passed down at the temple, the chief priest asked Ihachi to carve the “emptiness” in a quote from the Heart Sutra “form is emptiness, emptiness is form” (equivalent to “all is vanity”). It is the key phrase of this pivotal important Buddhist sutra and is interpreted to mean that nothing is permanent.

Ihachi depicted the emptiness overlapped by ephemeral, constantly changing waves. Apparently, he rode a horse into the sea over several days in order to observe the waves until finally he saw jewels floating on the ocean.

Jewels are symbolic in Buddhism, but while they frequently appear in the hands of Buddha or dragons, they never play a leading role. The truth of the story cannot be ascertained, but there is no doubt that the realistic composition of the “tunnel” under the breaking wave was inspired by actual waves.

Was Hokusai’s Great Wave Based on Ihachi’s Carving?

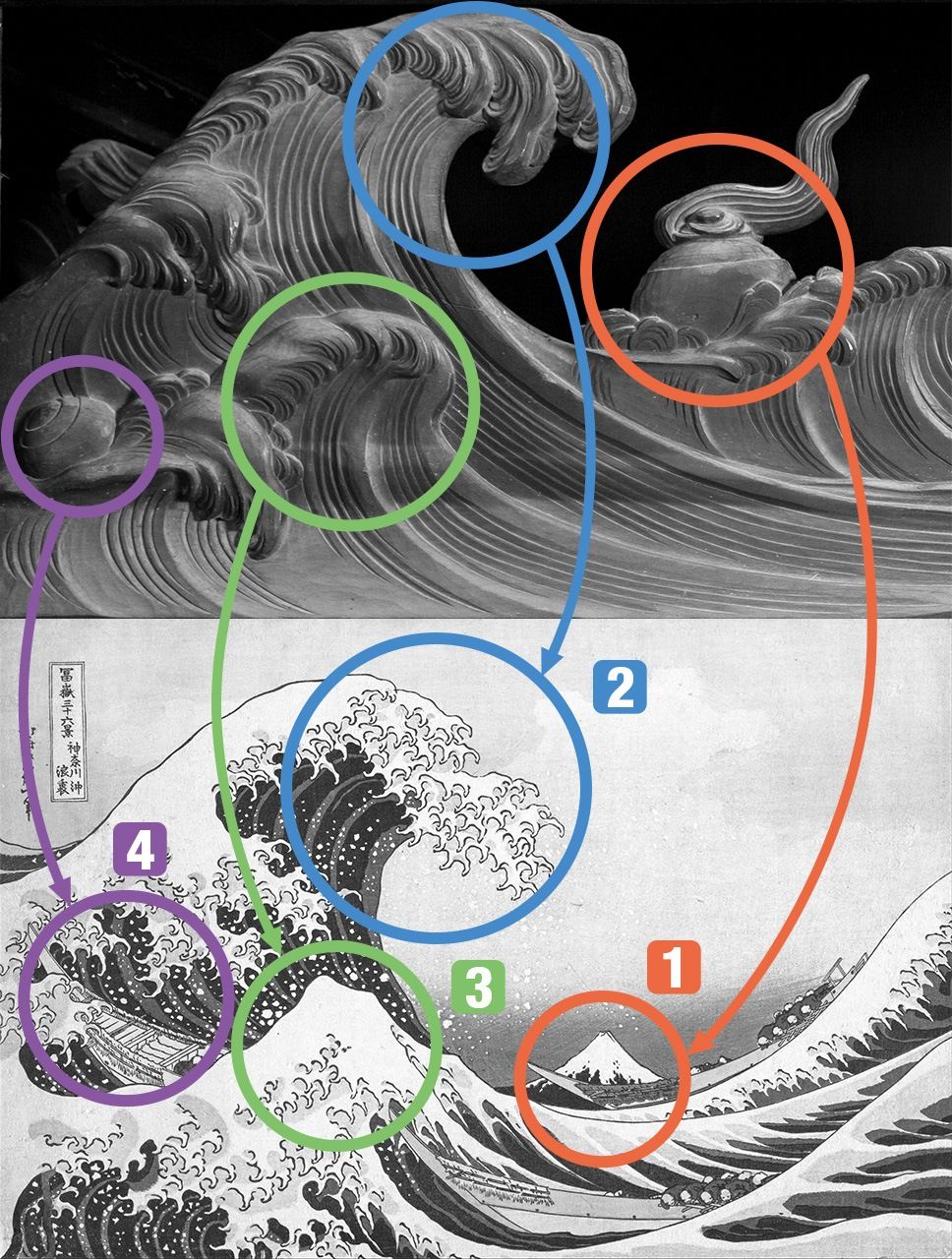

Kataoka Sakae, a researcher for Ihachi around 50 years, is a leading proponent of the theory that Hokusai’s Great Wave was an imitation of Ihachi’s work, and has written a book about the two artists. Viewed close-up, the resemblance with Jewels on the Waves is obvious. He points out that there are two main waves and explains how the details are arranged to suit the subject matter.

Jewels on the Waves (right-hand side, rear, detail) (Courtesy Ihachikai; © Odajima Nobuyuki); The Great Wave by Hokusai. (Courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; comparisons added by Nippon.com).

- The jewel with rising flames is replaced with Mount Fuji.

- The outline and engraved lines of the large wave are incredibly similar.

- The small wave is rearranged as Mount Fuji.

- The jewel showing its surface is replaced with a boat at the same angle.

Regarding how the time lapse from the emergence of the wave to its collapse is captured and expressed in a single print and sculpture, Kataoka believes that “Ihachi’s composition is ground-breaking. It surely can’t be a coincidence.”

There are also similarities in the techniques used. Hokusai claimed that “You can draw anything with a ruler and compass,” and in around 1812, he published a textbook, Ryakuga haya-oshie (Quick Lessons in Simplified Drawing), that explained the technique. The so-called compass-and-ruler technique is fundamental to carpentry. As a wood carver, Ihachi also used it for his creations: such as in his piece Nami ni tsuru ni asahi (Waves, Crane, and the Morning Sun), at Gyōganji, which expresses smooth, flowing waves.

Waves, Crane, and the Morning Sun. The wings of the crane and the morning sun appear to have been created using compasses. (Courtesy Ihachikai; © Odajima Nobuyuki)

Under Waves, Crane, and the Morning Sun, there is a picture by a student of Ihachi’s grandson Tsutsumi Dōrin, who specialized in townscapes, worked with Hokusai, and even lived with him for a time. Izunadera, the temple mentioned above, boasts a transom carving by Ihachi along with a ceiling painting by Dōrin himself.

Hokusai visited Bōsō Peninsula on more than one occasion. Kataoka suggests that he may have already heard about Ihachi’s waves from Dōrin. Ihachi’s work was so well known that other carvers in the Kantō region were reluctant to depict waves, “Hokusai wouldn’t have missed the chance to see it.”

But there is no historical documentation to prove any relationship between Ihachi and Hokusai, and only circumstantial evidence. “Both continued their quest to depict the dynamism of formless water throughout their lives, but Ihachi was the pioneer.” Kataoka hopes for a reevaluation of Ihachi. “Until now, the carver was considered inferior to the ukiyo-e artist, but finally he is gaining his share of the attention.”

Kataoka Sakae gives a lecture on the legacy of Ihachi. (© Nippon.com)

As the 200th anniversary of Ihachi’s death approaches, there is growing momentum to win greater recognition for him. In May 2024, a commemorative event was staged by a local group. Its leader, Shimizu Hiroshi, stresses that “Ihachi had close ties to this region, and produced work on a par with anything in Edo [now Tokyo].” He explained the group’s aim, “For the people of Kamogawa to inherit Ihachi’s spirit and apply it to community development.”

Top: A photo exhibition was staged at the venue by the Ihachikai “fan club.” Bottom: Shimizu Hiroshi speaks on behalf of the organizers. (© Nippon.com)

(Banner photo: From the photo book Edo jidai no chōkō shodai nami no ihachi ~ takeshi ihachirō nobuyoshi no sekai (The Edo-Period Sculptor Ihachi of the Waves: The World of Takeshi Ihachirō Nobuyoshi) Courtesy Ihachikai. © Odajima Nobuyuki.)