Learning and Loving the Japanese Language

Hiragana: The First Building Block of Written Japanese

Language Culture- English

- 日本語

- 简体字

- 繁體字

- Français

- Español

- العربية

- Русский

Thrills of Recognition

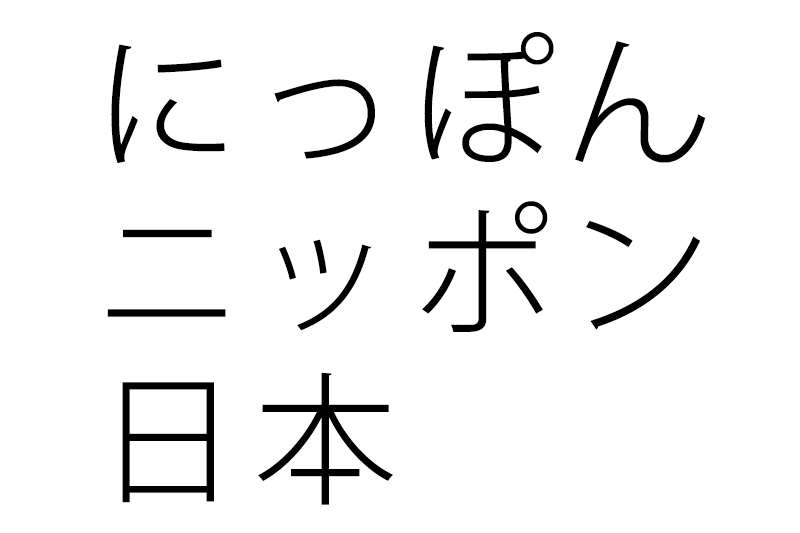

Nippon or “Japan” written in hiragana, katakana, and kanji, respectively.

Nippon or “Japan” written in hiragana, katakana, and kanji, respectively.

The Japanese language has three main scripts, and the most basic and essential of these is hiragana. Children learn its 46 characters while they are preschoolers, before they go on to tackle katakana and kanji. It is straightforwardly phonetic, meaning the characters always have the same basic pronunciation, so is easy to put to use right away—there is not the same initial hurdle as found with English spelling. Each of the characters represents a different short sound, almost always ending with one of the five vowels a, i, u, e, and o. Only one, representing n, does not include a vowel sound.

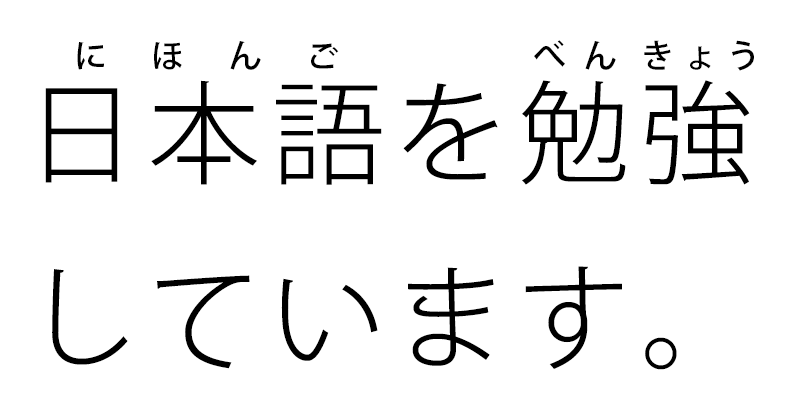

Small characters, known as furigana or rubi, above the kanji give their pronunciation. Nihongo o benkyō shite imasu (I’m studying Japanese).

Small characters, known as furigana or rubi, above the kanji give their pronunciation. Nihongo o benkyō shite imasu (I’m studying Japanese).

As a foreign learner, it is possible to get by for a while studying Japanese written in Roman letters (rōmaji). With only just over twice as many as characters to learn as letters in the alphabet though, it is worth making the effort to master hiragana early. It is the foundation for further reading and is used to indicate the pronunciation of kanji that the reader is not expected to know. Understanding hiragana is also the basis for the first thrills of recognition in a Japanese-language environment.

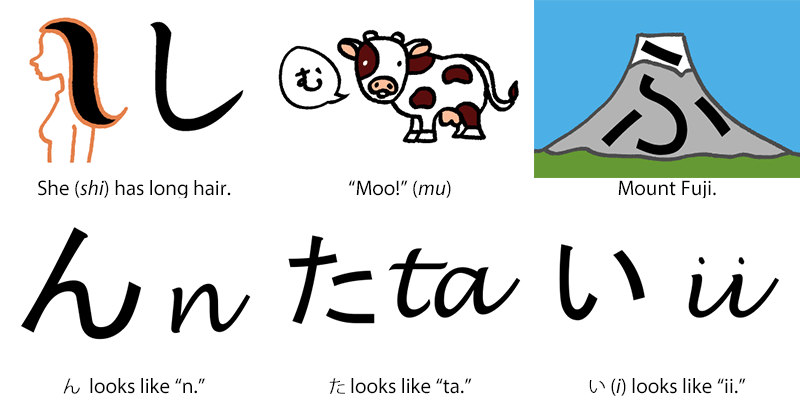

Mnemonics speed up the learning process, although some hiragana are easier to memorize than others. With し (shi), for example, observing once that “she has long hair” may be enough. Other characters might need a little more time and imagination. A few are more or less similar to their alphabet equivalents, such as ん, which resembles a stylized “n,” and た, which is close in shape to “ta.” The kana い (i) looks like a couple of undotted “i”s standing together.

My favorite picture mnemonic is for む (mu), which looks like a cow—the head on the left and the tail on the right—famous for saying “moo.” The kana ふ (fu) appears somewhat like Mount Fuji. It is easy to find further examples online by searching for “hiragana mnemonics.” If the problem is getting similar kana mixed up, such as さ (sa) and き (ki), れ (re) and わ (wa), or は (ha) and ほ (ho), focusing on the differences, like the extra lines in き and ほ, helps to prevent confusion.

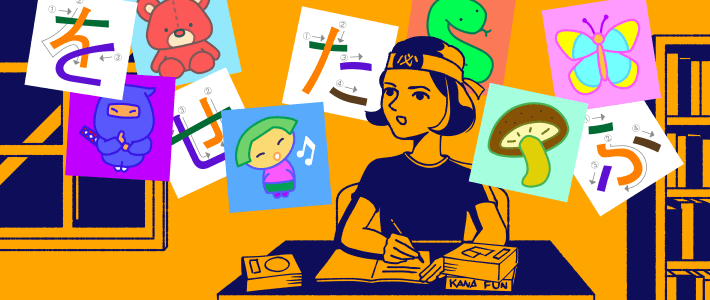

Getting It Down on Paper

The ability to write hiragana in Japan remains essential, even as we spend more time tapping on screens. Writing reinforces reading too, so there is no reason to hesitate. Japanese children learn through repeated drilling, and while many learners use apps or other digital tools to pick up the kana, there really is no better way to make the lesson stick than to sit down and write them out by hand. Examples of practice worksheets available online can be found at Chibimusu Doriru. These provide a good starting point for self-study.

Elementary school teachers tend to be strict on children getting the strokes looking exactly right and writing them in the correct order. My own opinion on stroke order (for katakana and kanji too) is that it is best to try to learn it correctly in the early days, but as long as the final result looks the same, it is not necessarily a big deal. Note, however, that getting the characters to look right can depend on whether you write them in the proper order; incorrect stroke order can also cause problems in character recognition when drawing with a finger or stylus on phones and tablets.

It is worth noting that some characters look different in their commonly printed form compared with when they are written by hand. While き and さ appear to be joined together in print, as seen in cursive calligraphy styles, there is usually a space between the near vertical and lower horizontal lines when handwritten (see the chart below).

Association and Memorization

Having learned the basic characters, there is still a little way to go. Two short strokes to the right of a kana transform its consonant from unvoiced to voiced—so, for example, か (ka) become が (ga). Entries in the は (ha) column change to begin with a “b” sound, as in ば (ba), and can also transform to begin with a “p” sound through the use of a small circle, as in ぱ (pa). Kana can form combinations, such as しゃ (sha) and きょ (kyo). Finally, a small っ indicates a short pause between sounds, represented as a double consonant, such as てっぱん (teppan).

Memorizing hiragana (and other scripts) is easier in context. It is quite common to recognize characters immediately in a favorite word, but struggle with them in a less familiar term. Associating the kana you find difficult with a well-known item of vocabulary can help them to stick. Encountering and reading words in your daily environment is also excellent for memorization. Living in Japan is ideal and greatly reduces effort, but taking every opportunity to spot hiragana in anime or printing words to memorize and placing them around the home can also be effective.

There is no popular equivalent to the alphabet song for learning the order of hiragana: a, i, u, e, o, ka, ki, ku, ke, ko, etc. It is useful to know that, for example, は (ha) comes before ま (ma) but after な (na) when searching ordered lists, flipping through a Japanese dictionary, or finding one’s way around a music store. Perhaps the easiest way to get a good basic grip is to practice learning with a chart arranged to show the order, as given below.

The “Iroha poem” is a famous verse written around 1,000 years ago, featuring all the kana once each and expressing a Buddhist message about the transience of life. Its name comes from its first three syllables, i, ro, and ha, and was once used to order the kana. Although the order is no longer generally used, and includes some kana that do not usually appear in modern Japanese, it can still be seen in children’s card games.

(Originally written in English. Illustrations by Mokutan Angelo.)